Lantern Slides and Glass Plates

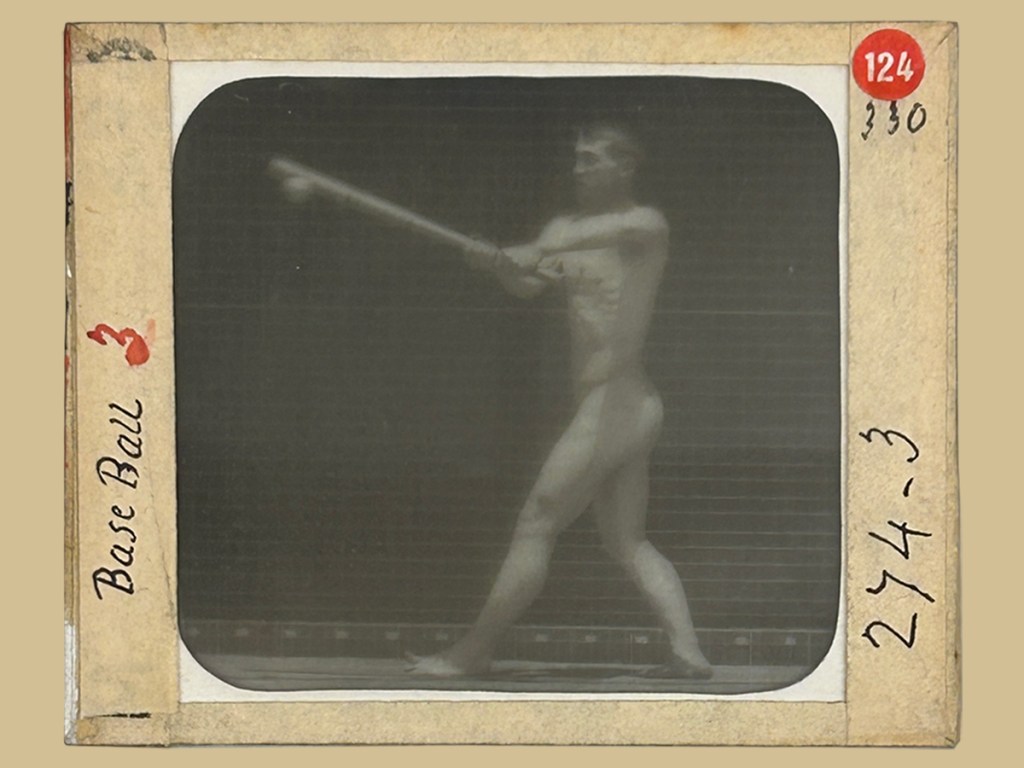

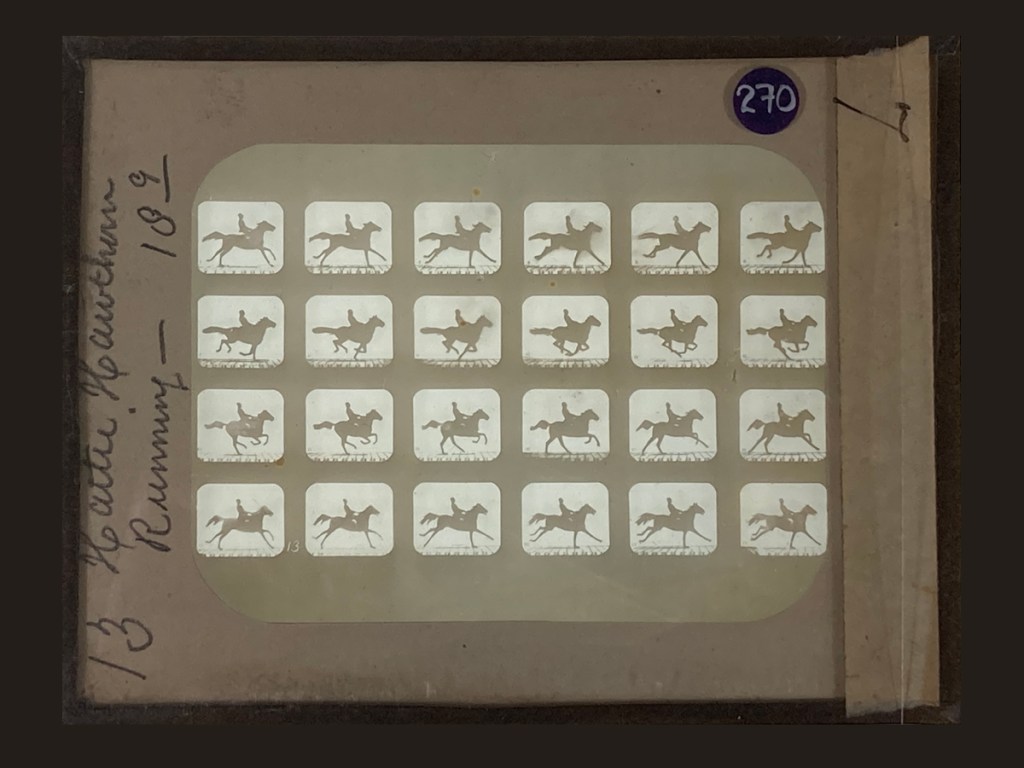

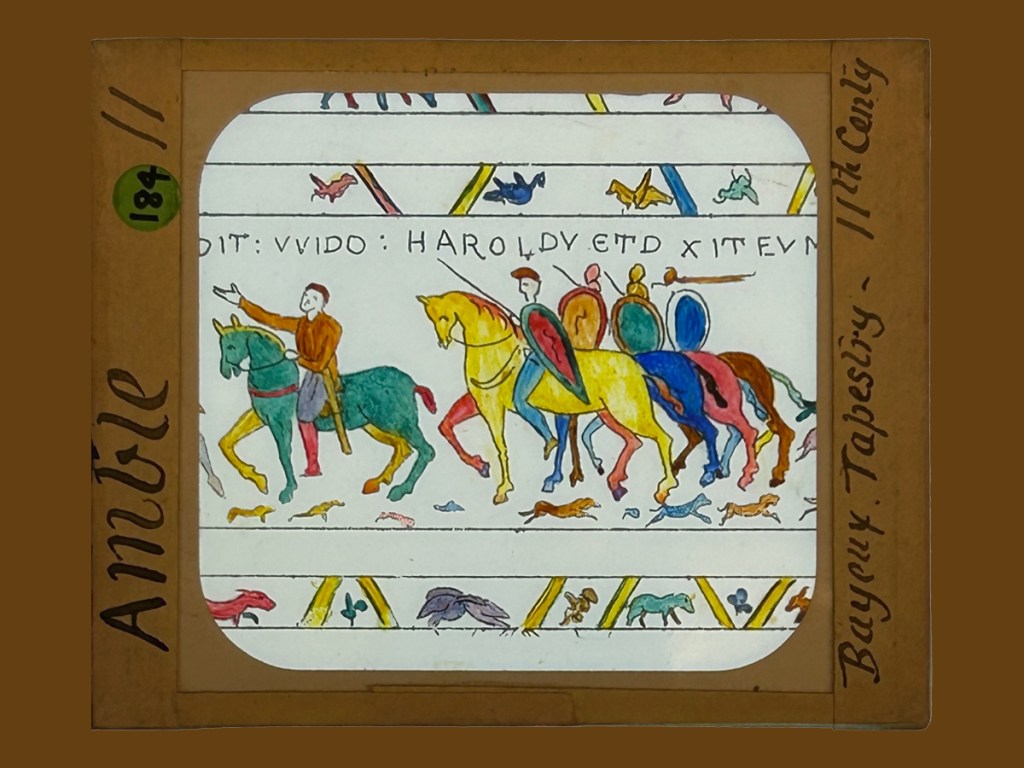

The most significant portion of the Kingston Museum’s Muybridge Collection consists of over 2,200 glass lantern slides and unmounted glass plates. More than 1,300 of these relate to the photographic motion studies of humans and animals, which Muybridge first conducted in California during the 1870s and later in Philadelphia in the 1880s. Most of these images appeared in Muybridge’s major publications, The Attitudes of Animals in Motion (1881) and Animal Locomotion (1887). The museum’s collection also includes many unpublished images, some of which are unique to the Kingston Collection. Another noteworthy aspect of the collection is the more than 400 lantern slides that contain historical and contemporary reference images. Muybridge displayed them alongside his own images during his lectures to illustrate the accuracy of his work.

The museum’s collection also includes over 400 lantern slides and glass plates featuring Muybridge’s landscape photographs, ranging from his early work in the late 1860s, including those taken in Alaska, to the 1878 San Francisco Panorama. However, a significant portion of the landscape images was captured in Central America. Muybridge took these photographs in 1875 on commission for the Pacific Mail Steamship Company. It seems that Muybridge created many of these glass plates from stereographic photographs, which may explain the presence a number of duplicate plates in the Kingston Museum’s collection.

Lantern slides and glass plates of Muybridge’s images are rare, with only about half a dozen institutions possessing them in their collections. The extensive collection of these materials enhances the significance and prominence of the Kingston Museum’s Muybridge Collection.

‘Amble. Bayeux Tapestry 11th Century’

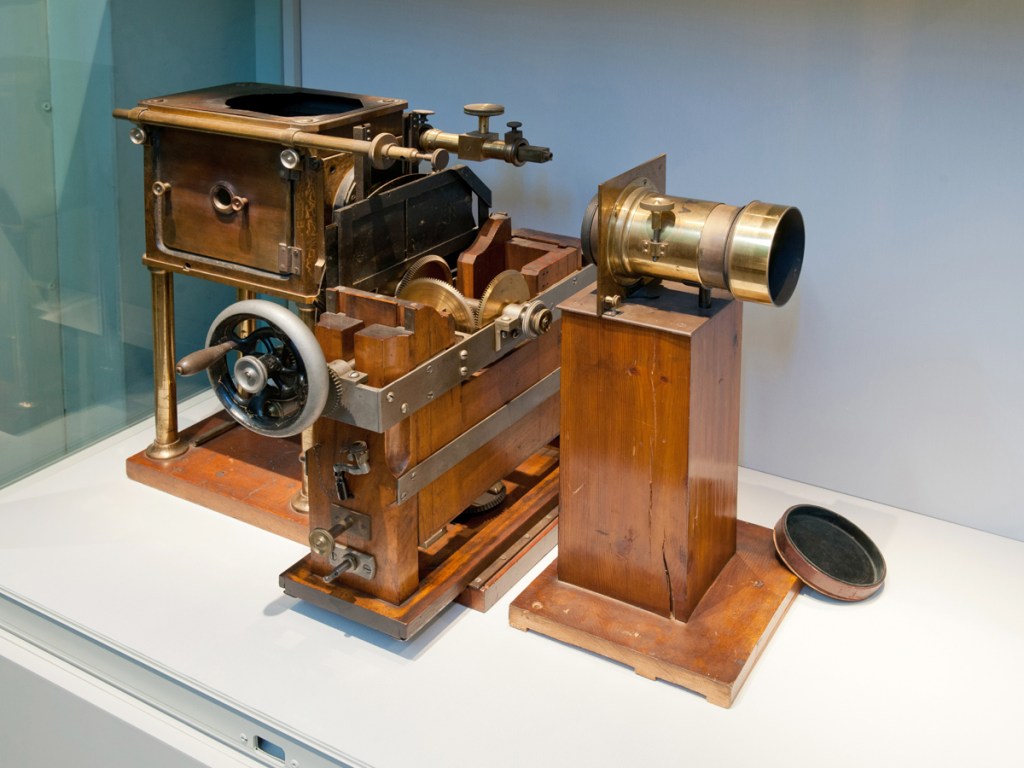

Zoopraxiscope and Discs

Kingston Museum houses the only known original Zoopraxiscope, a pioneering moving image projector created by Muybridge, along with 69 surviving discs: 35 discs with a diameter of 16 inches and 34 discs with a diameter of 12 inches.

Muybridge’s pioneering photographs of moving horses truly impressed people, but some questioned the accuracy of his work. He sought to establish the credibility of his images. In 1879, Muybridge devised a moving image projector that could recreate the motion of a horse from his photographs. He initially called it the ‘Zoogyroscope’ and later renamed it the ‘Zoopraxiscope’ (meaning “life-action-view” in Greek). It consists of three parts: a lantern body, a mechanism in a wooden frame, and a mounted lens.

The Zoopraxiscope was one of the first moving image projectors. Many people may not have experienced realistic moving image projection before. Witnessing a life-size horse galloping continuously on a screen would have been a magical experience. Since his first public demonstration of the Zoopraxiscope on 4 May 1880 at the San Francisco Art Association, Muybridge performed hundreds of projection lectures for various audiences in the UK, America, and Europe. These lectures were attended by the general public, artists, scientists, and even royalty!

Muybridge arranged his images along the edge of a glass disc. When the disc spun in the projector, a moving horse appeared on the screen. Unfortunately, his original photographs could not be used because they appeared squashed when viewed through the projector. To compensate for this distortion, Muybridge elongated his images and traced them onto the disc. In his later publication, Animals in Motion (1899), Muybridge evaluated his apparatus: “It is the first apparatus ever used, or constructed, for synthetically demonstrating movements analytically photographed from life, and in its resulting effects is the prototype of all the various instruments…” Details of how Muybridge created the discs can be seen in this short video, ‘Muybridge’s Zoopraxiscope: Setting Time in Motion’, created by Chocolate Films. You can also learn more about the Zoopraxiscope’s construction and operation from this short video, produced by Muybridge scholar Stephen Herbert.

The early discs, produced around 1880, had a diameter of 16 inches, with the silhouettes of the images painted in black. In 1893, Muybridge participated in the Chicago World’s Fair to present his projection lectures. Unfortunately, this endeavour failed to attract large crowds. In the same year, he made new discs with a reduced size of 12 inches. He also coloured the discs, presumably to make his moving images more appealing and engaging. Muybridge, however, later regretted creating those coloured discs and wanted to destroy their negatives. Fortunately, 51 negatives have survived and are now part of the National Museum of American History’s collection. Visit here to see details of these negatives. Despite his regret, Muybridge retained the 12-inch coloured discs. He bequeathed all the discs in his possession, both the 16-inch and 12-inch ones, to Kingston Museum.

The image was taken c. 1895

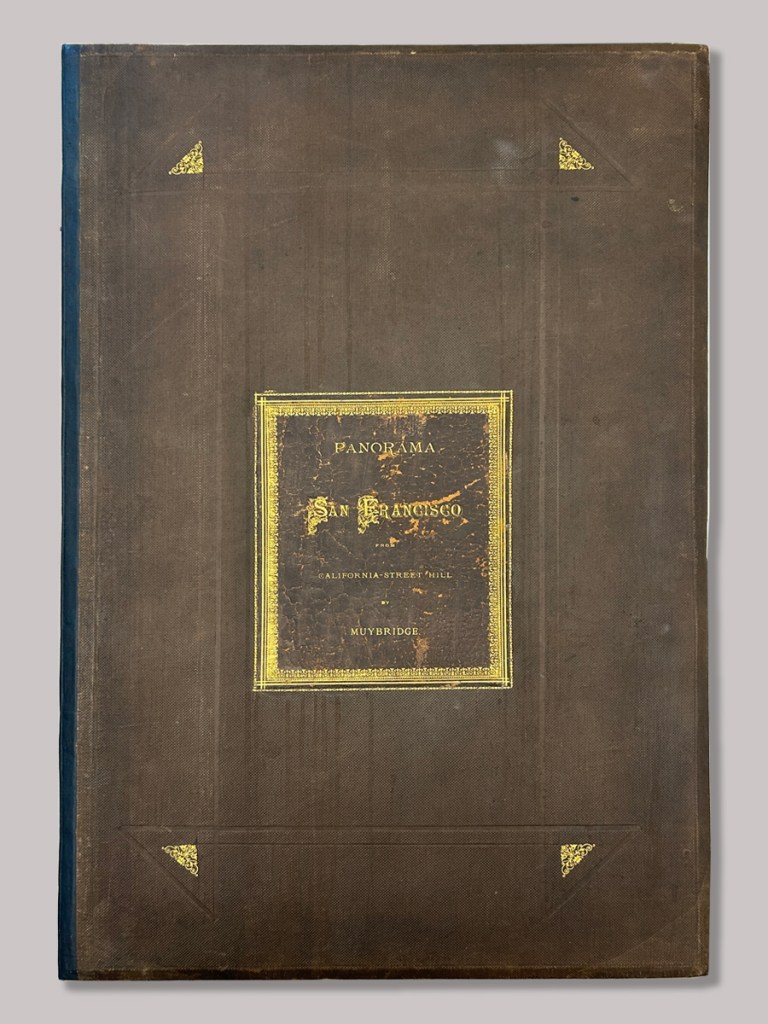

1878 San Francisco Panorama

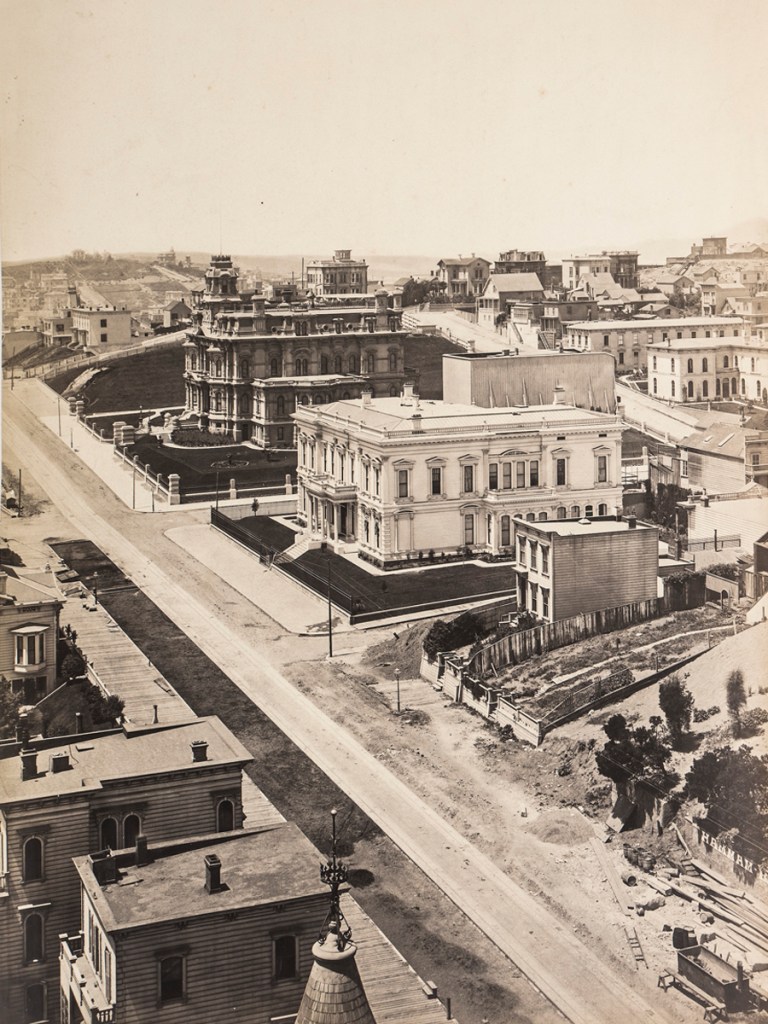

In 1877 and 1878, Muybridge photographed San Francisco from the top of the newly built Mark Hopkins mansion on California Street Hill, also known as Nob Hill. At 381 feet (116 m) above sea level, it was the highest point in the city at that time. Muybridge’s 360-degree panoramas are outstanding visual records of San Francisco’s ‘Golden Era’, illustrating scenes of its social history, business, and culture in great detail. The 1877 panorama is an eleven-part album, with each plate measuring 8.5 x 12 inches (21.5 x 31 cm). Many copies of this panorama were made and sold.

In 1878, Muybridge produced the most ambitious panorama of the city. The thirteen-part panorama, consisting of thirteen 20 x 24-inch (50.8 x 61 cm) mammoth plates, measures approximately 17.5 feet (5.33 m) in length when laid out flat. This seamlessly joined, expansive panorama showcases Muybridge’s remarkable technical achievement. Nine copies of this panorama are known to exist, with the Kingston Museum’s copy being the only one outside the United States.

Muybridge began photographing the southwest view in mid-morning. Working in a clockwise direction at intervals of approximately 15 and 25 minutes between plates, it would have taken him four to five hours to complete all thirteen photographs. Taking images with the wet-collodion process and large glass plates at such a pace would have been a technical challenge. Muybridge likely had at least one assistant helping him during this process. Interestingly, after taking all the images from plates 1 to 13, Muybridge rephotographed plate 7 for unknown reasons, as evidenced by the direction of the lighting and shadows in the image. He trimmed the thirteen plates of albumen silver prints to 16 x 22 inches. He mounted them on paper and backed them on a single sheet of linen to produce an accordion-folded album.

The panorama depicts the fascinating historical scenes of San Francisco in the late 1870s. A notable example is the infamous ‘spite fence’ captured in plate 3. Charles Crocker, who owned a mansion on California Street Hill, built a three-sided fence around Nicholas Yung’s house because Yung refused to sell his house to him. Charles Crocker, Leland Stanford, Collis Huntington, and Mark Hopkins funded the Central Pacific Railroad. These railroad tycoons are commonly referred to as ‘The Big Four’.

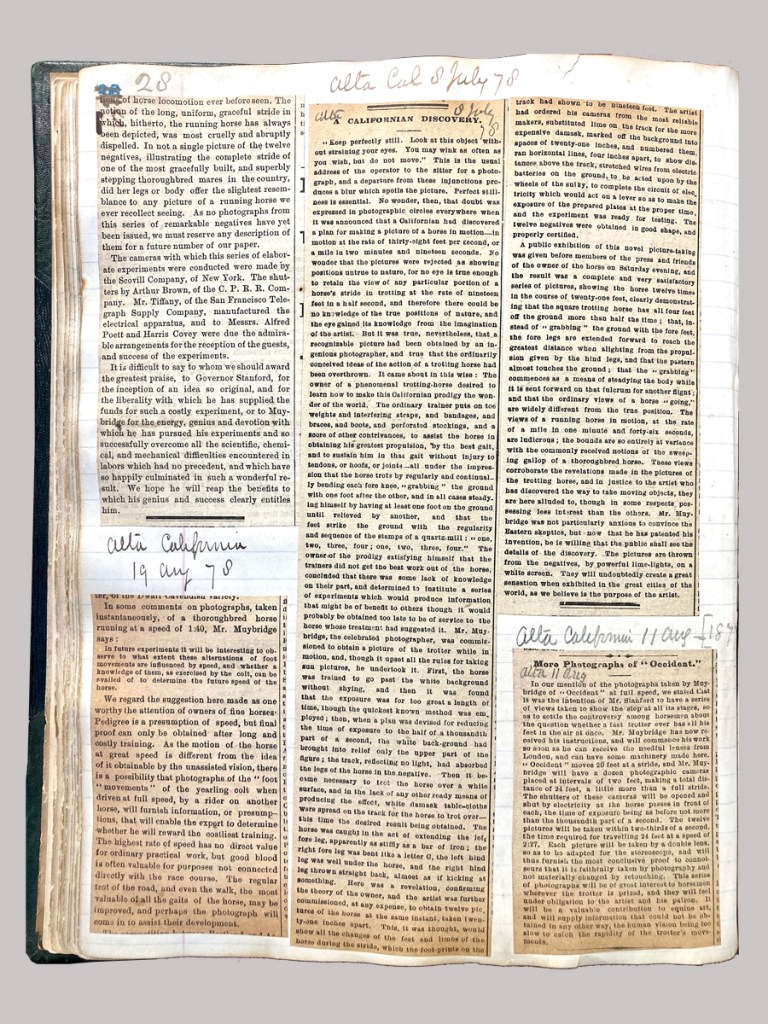

Scrapbook

Kingston Museum’s Muybridge Collection is a comprehensive assembly of Muybridge’s work, spanning around two decades as a photographer and 15 years as a lantern lecturer. One item in the museum’s collection that best represents this is Muybridge’s scrapbook. Following the first entry about his photograph of Yosemite in 1868, the scrapbook contains 257 pages filled with newspaper clippings of announcements, reviews, and articles related to Muybridge’s works and associated matters. It also includes numerous additional folded and bound materials, such as leaflets and brochures, inserted between the pages. Its rich content makes it one of the most valuable and comprehensive resources on Muybridge’s work.

The scrapbook is both autobiographical and selective in nature. Similar to a portfolio, its purpose is to highlight Muybridge’s accomplishments. Muybridge treasured it so much that he offered to pay $10 or £2 for its safe return if it were lost! The scrapbook continued to be cherished by Kingston after it was initially deposited at the Kingston Library and later at the museum. Nine additional entries were added to the scrapbook after Muybridge died in 1904. The first five were likely added by the museum’s first curator and Muybridge’s friend, Benjamin Carter. The museum’s second curator, Harry Cross, would have entered the other four, including the last one, in 1930.

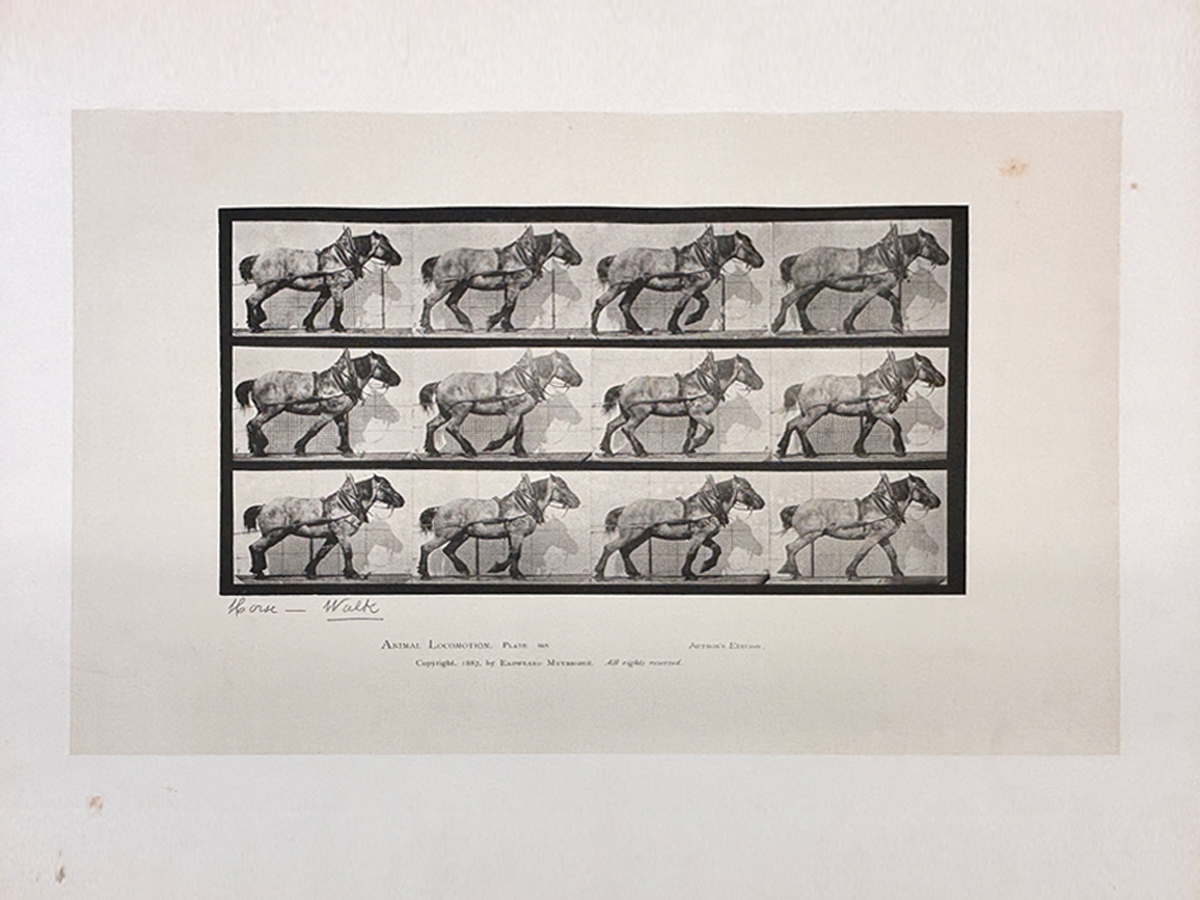

Author’s Edition of Animal Locomotion

Together with the publication of his most ambitious work, Animal Locomotion (1887), Muybridge also produced a small number of ‘Author’s Edition’ bound portfolios of selected collotypes. Kingston Museum holds a rare copy of this ‘Author’s Edition’ portfolio in its collection. Muybridge presented it to the Kingston Library in January 1896, which was later transferred to the museum. A complete portfolio consists of 21 plates, comprising 12 of humans and 9 of animals. However, the Kingston copy contains 20 plates, missing plate 408.

It is unclear how many of these special portfolios Muybridge created, but three institutions – Kingston Museum, the Royal Academy in London, and the George Eastman Museum in Rochester, NY – are currently known to hold one copy each in their collections. This suggests that Muybridge brought at least two copies to the UK. Unlike Kingston’s copy, which was originally gifted by Muybridge, the Royal Academy’s copy was initially presented to E. H. Dring, a book dealer in London, and was later acquired by the Royal Academy. Visit here for more information about this copy.

Throughout his career, particularly in his later years, Muybridge was keen to present many of his works to various institutions and individuals. The Kingston Bequest was undoubtedly his most significant and purposeful effort to leave his mark.

The Attitudes of Animals in Motion

In 1878, Muybridge published the results of his groundbreaking photographic experiments conducted at Stanford’s Palo Alto stock farm in a set of six cabinet cards titled The Horse in Motion. Muybridge gained international acclaim from these instantaneous images. The following year, he expanded his experiments by photographing many more horses, as well as other animals and humans engaged in various actions. In 1881, he compiled the results of his work into an album containing 203 plates of images, titled The Attitudes of Animals in Motion: A Series of Photographs Illustrating the Consecutive Positions Assumed by Animals in Performing Various Movements [Attitudes].

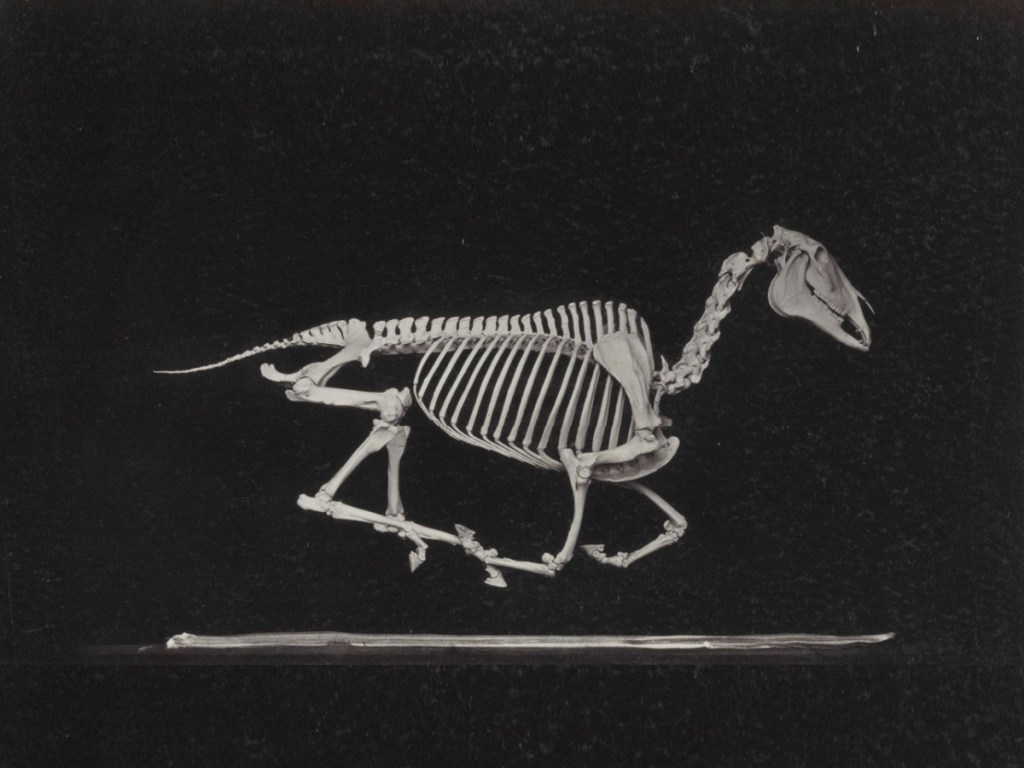

A complete copy of Attitudes consists of 173 pages, including a three-page index of illustrations. The index provides information about the image content, such as descriptions of actions, the length of the stride, and the horses’ names. The following six pages contain images that depict the details of Muybridge’s studio setup and the cameras used in the experiments. The remaining pages comprise 203 plates of Muybridge’s photographs, including ten plates of individual images of a skeleton horse in different movements.

Muybridge produced a limited number of copies of Attitudes, primarily for presentation purposes. Kingston Museum holds two copies of this rare and important early work by Muybridge on motion studies. These copies are special because they were the creator’s personal belongings. The differing appearances of these copies further enhance their uniqueness. In contrast to other presentation copies, which feature more elaborate bindings, the Kingston copies have simpler covers. Their evident signs of use also suggest that they were likely Muybridge’s working copies.